Ignoring The Reward Matrix

The power of literally not caring about incentives

Out of all the time I spent working alongside high ranking military officials in my formative years, and throughout all the meetings and dealings I’ve had with incredibly smart entrepreneurs and investors in my adulthood - nothing taught me more than that one time in highschool a kid smacked our geography teacher for getting a haircut.

My highschool was a mix of clueless middle class kids, gentle and childlike, and kids from the literal toughest parts of town - those who had clearly had life throw some heavy punches at them, and had already gotten used to punching it back.

This unholy mix of adolescents was then thrown into a volatile petri dish of hormones and aggression for six years, while adults crossed their fingers and hoped for the best.

It was survival of the fittest, and this applied to the teachers too. An uncomfortable proportion of which, for the full 6 years I was there, never once managed to get a class under control (let alone fathom what students were up to during recess). I used to judge them for it. Looking back at it now I’m much more emphathetic.

We had kids that stab, kids that get stabbed, some were related to well known crime families - some heavy shit. I once witnessed a classmate get a brick to the face, come back the next day with his head shaped like a balloon, and shake hands with his assaulter to settle the beef (since to be fair, the brick only got involved after the former had sucker punched the latter).

Meanwhile, I learned that in the jungle my main strengths were more akin to a lizard’s - use my tongue, and failing that, nimbly scamper out of reach.

Back to the story: the kid in question, who we’ll call E, was one that always hung with the toughest crowds in school. He was a couple of heads shorter than most, and made it a point to make up for whatever he lacked in height with muscle mass and hostility. He was always on the lookout to start or join a fight, and while your first instinct might have been to laugh at him, we all quickly learned not to.

Luckily, he seemed to have a soft spot for my friend group (I suspect because on some level he always craved a certain kind of emotional dialogue which his friends didn’t provide). He helped us out of a few tricky situations, and in some weird butterfly effect I probably owe him my life (a story for a different time)!

As he once confided in me, he had experienced his fair share of bullying in elementary school for being smaller, until one day he snapped. He realized that if you’re truly vicious enough - you can outbully the bullies. All you had to do was dare. Indeed by the time I met him he had climbed the social pecking order of the school through his own unique mix of violence and charisma.

Such was his origin story, and depressing or inspiring as it may be - he never hesitated to punch neither above nor below his weight.

Now that you know about the character in question, all that’s missing is the following knowledge: one of the ancient codes of our grade was that if you ever saw a kid with a recently acquired haircut, you’d be obligated to smack the back of their neck as many times as their age.

In theory as hard as you can, in practice after the first few good hits you’d usually devolve into more of an aggressive sweeping motion to wrap things up quickly. As you can imagine, not all kids enforced this, but those who did did so with great devotion and glee.

And so the stage is set:

I remember it distinctly. I was sitting on the 3rd row in the middle of the class, and our geography teacher, a slim, meek, sinless man who always seemed a bit lost, was sitting slumped in his chair trying to teach us some nonsense about peninsulas. Most of the class was chattering away unbothered. All of a sudden E exclaims all the way from the back “Hey *teacher’s name*! Did you get a haircut”?!

“Actually yes!” the teacher replied, jolting up from the excitement of having had something personal about him be noticed by a student.

E was already halfway across the classroom by the time he answered, swiftly and confidently planting himself behind the teacher’s chair. He initiated the ritual. “1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 ,8…” he counted as fast as he could under his breath as he smacked his hands back and forth across our teacher’s neck with maximal focus. While he certainly wasn’t using too much force, our teacher’s head was bopping up and down with each hit.

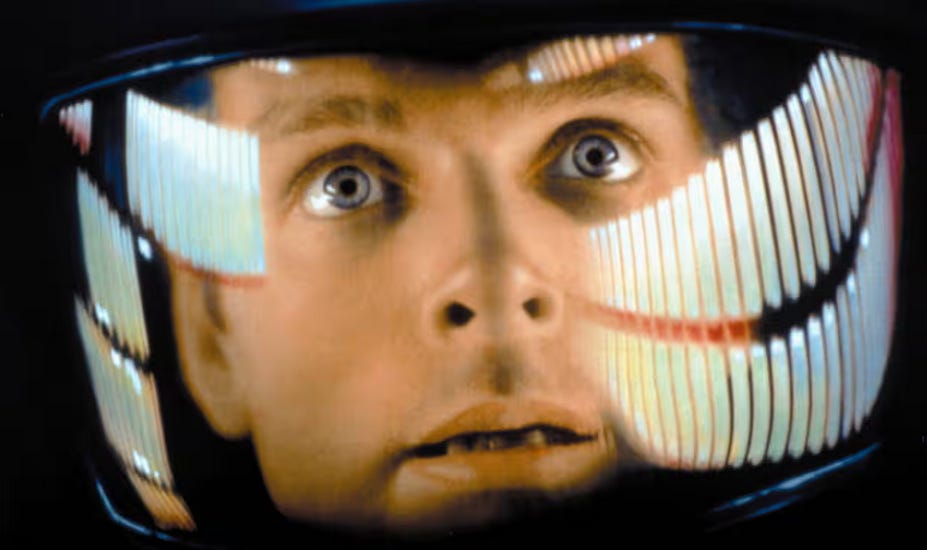

Teenage me meanwhile, was sitting wide eyed and slackjawed watching in disbelief. Most of all, I remember feeling nauseous. I couldn’t look away. The teacher was initially too stunned to react, and E meanwhile, aware that what he was doing was pushing his luck (yet determined to see things through till the end nonetheless), continued all the way up to double digits before the teacher thought to shove his hand away with his elbow.

Not furious, not punitive, just annoyed. Exclaiming “stop it!” with the same reservedness that any other kid who was afraid of getting beat up would have emitted. E then laughed, patted him on the back as if they were friends, and returned to his business at the back of the class.

The teacher then shyly resumed, with heroic optimism, his attempt to continue the lesson. As if nothing had happened. Yet the chattering continued uninterrupted until the bell rang for recess. I don’t think most of the class even noticed the event, let alone given it much weight.

Meanwhile, my adolescent brain had been irreversibly rewired. Truly, deeply, internalizing it’s first edgy “Life 101” conclusion:

Rules. Are. Fake.

What shocked me even more however, was how comfortable E was throughout it all. For me it was unthinkable, literaly reality shattering. For him it was just an action that took place today. He didn’t see a school with teachers and students - he saw a concrete structure with people in it. Some he liked, some he didn’t, some he could bully and some he could not.

He had his own set of internal drives that were meaningful to him, and whatever unique incentive structures and norms existed in this building’s territory (study, pass tests, avoid punishment) were factored out of his decision making. Unafraid of neither the rewards nor the penalties.

This unhindered way of seeing things came to him as naturally as a cat sees the top of a wardrobe as a legitimate spot to jump to, or as casually as a bear strolls onto a front porch - seeing something for what it is, completely free of context.

It’s a form of X-Ray vision for societal structures. This (morally neutral!) ability to see the world is the same one utilised by transformative leaders - whether in politics, social revolutions, entrepreneurship - along with most criminals, and anyone whose ever had to improvise food and shelter from scratch.

It’s the ability to see base level reality, along with all the complex abstract incentives superimposed upon it, and to then just choose to discard them - paying attention only to the base. It’s the necessary first step for any real change (or exploitation) of a given situation to take place - identify what the hell you’re looking at for what it really is.

Simply through exposure to E, something was unlocked in my mind that I could never unsee again. School had stopped embodying, and being experienced as a "School" (along with its associated goals and societal context). It had irreversibly transformed into a crumbling building full of lost kids and depressed teachers. The veil had been lifted, and I could no longer see its demands and promises in the same way.

In a way I truly believe it’s akin to a superpower, and like any superpower, it can be abused (as E was always happy to demonstrate), or used for the greater good.

The ability to genuinely not care about a given incentive structure, and to define your own (while inherently risky) provides an outrageously disproportionate advantage in terms of agency, practicality, and capacity to navigate reality. It’s not even about “thinking outside the box”, it’s more like you’re standing outside of the box and looking into it. Or maybe not even looking at the box at all, and just checking out what other objects are laying around the room.

It’s the difference between being defined by, defying, and defining incentive structures - and E was a natural at it.

The end! If you made it this far, please feel at home - you’re officially among friends! You’re super invited to join the next adventure (and comment whatever you want below)!

As always - a heartfelt welcome to all the brave new subscribers since last time! It means the world to me whenever one of you decides to stick around. Thank you with all my might!

Those who can’t act independently of a given incentive structure are ruled by it. If you have the internal discipline and skillset to forge new structures of your own, go for it (just please make sure they’re positive sum ones)!

Thanks for the post. I liked this bit very much: "the ability to see base level reality, along with all the complex abstract incentives superimposed upon it, and to then just choose to discard them - paying attention only to the base."